migration of mesenchymal stem cells

After the defence of my PhD thesis, I continued looking at how particle-based models could be applied to a wider range of materials. I stayed a few more months at the Laboratoire de Mécanique et Technologie to model fracture in masonry, which could be seen as a very organised type of concrete. But I rapidly realised that these methods could be applied to drastically different systems, and actually a living one: stem cells. That is when I joined the Groupe Interdisciplinaire en Biomécanique Ostéoarticulaire at Aix-Marseille Université.

the science

It’s been quite a while now that we have understood that the behaviour of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is controlled by very specific physical cues. Chemical cues are by far the most explored, and that’s what drugs rely on. But mechanical cues are more and more explored, they are now known to influence migration, differentiation, mitosis, and apoptosis of cells. The properties of the environment of the cell, its shape or its stiffness for examples, can potentially determine the complete cellular life cycle. Unraveling the physics of these mechanisms, establishing the chain of events from the mechanical constraint to the observed behaviour, is essential to pave the way toward physics-based biomedical and tissue engineering.

We took the project over at the stage where biophysicists were trying to understand how the curvature of the substrate is directing cell migration. As we had no clue on the driving force of cells and therefore nothing to model, we first studied adherent cells. Modelling MSCs adhesion in hemispheres, and comparing the establishment of force networks in the cytoskeleton, we showed that cells are in lower energy state (relaxed) when found in holes instead of on bumps. For cells seen as an assembly of membranes, viscous fluids and tensed cables hollow areas represent more stable environments. Therefore our static model implied that concave topographies are probably more suited for biological purposes such as division, which would benefit from reduced sensitivity to mechanical perturbations [1].

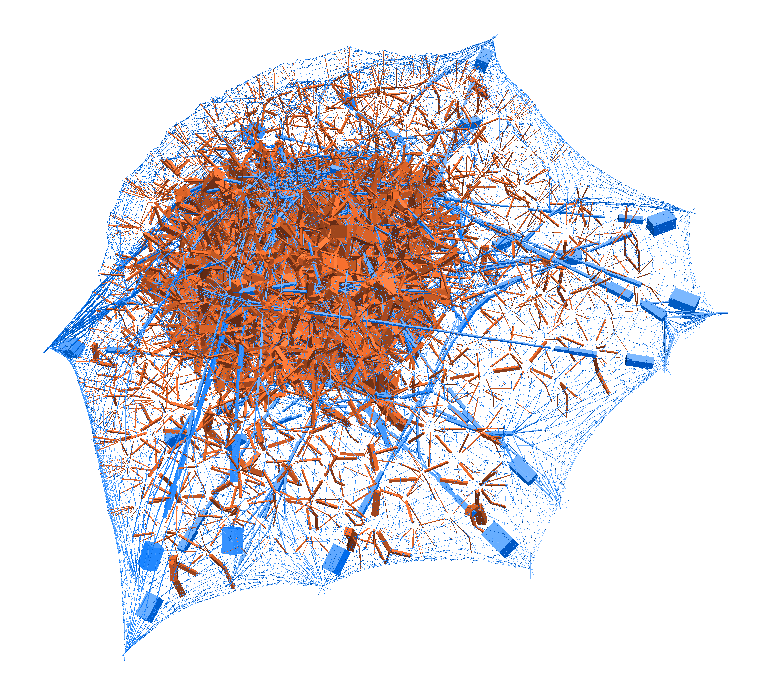

laziness at its finest: (left) a mechanical model of cell migration on a sinuous surface showing how stem cells avoid convex, hilly topographies; (right) force network in the cytoskeleton of an adherent cell (blue: tension, red: compression).

We then looked at cells in adhesion on asymmetric topographies, that is not perfectly centred on a hill or a hole. We observed experimentally and computationally that cells nuclei was pushed away from the most convex curvatures. From there we hinted that migration could be induced by an off-centred position of the nucleus. Integrating that mechanism in our model, we were able to reproduce consistent migration of adherent cells on sinusoidal topographies. Our simulations reproduced experiments realised by L. Pieuchot [2] and shared within the ANR-SinusSurf collaboration. In silico and in vitro, MSCs were shown to migrate toward hollow areas and, under forced migration, systematically avoiding hills [3]. Deeper insights from simulations showed that cell polarization via the off-centred position of the nucleus could be explained by anistropic pressure gradients inside the cytoskeleton originating from the curved substratum.

Being able to determine systematic migration patterns of MSCs was a first interesting step, but much remain to be explain, wether such behaviour can be explain by purely physical consideration, or wether it is an active cellular mechanism involving signalling pathways. Understanding the relation between extracellular cues and lower scale molecular mechanisms will certainly be an efficient solution to draw further insights. Tissue engineering and biomaterials design, via scaffold engineering, could benefit from these advances and provide test cases to validate drawn hypotheses.

the devs

All the required pieces of software that I used to develop the stem cell mechanical model could be found in the LMGC90 library. The cell model itself has been built using the tensegrity theory which describes the cytoskeleton as an assembly of load bearing beams and initially tensed cables, surrounded by viscous fluids and elastic membranes. The model has been calibrated and checked against experiments as part of a publication [1], and made available as an open-source repository.

the publications

[1] Maxime Vassaux and Jean-Louis Milan.

Stem cell mechanical behaviour modelling: substrate’s curvature influence during adhesion.

Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology, 16 (2017): 1295-1308.

[2] Laurent Pieuchot, Julie Marteau, Alain Guignandon, Thomas Dos Santos, Isabelle Brigaud, Pierre-François Chauvy, Thomas Cloatre, Arnaud Ponche, Tatiana Petithory, Pablo Rougerie, Maxime Vassaux, Jean-Louis Milan, Nayana Tusamda Wakhloo, Arnaud Spangenberg, Maxence Bigerelle and Karine Anselme.

Curvotaxis directs cell migration through cell-scale curvature landscapes.

Nature Communications 9 (2018), Article number: 3995.

[3] Maxime Vassaux, Laurent Pieuchot, Karine Anselme, Maxence Bigerelle and Jean-Louis Milan.

A biophysical model for curvature-guided cell migration.

Biophysical Journal, In Press (2019).